Note: I originally wrote this in 2014, so adjust numbers for inflation.I’d like us to become a post-scarcity society. Most people probably do. Well, most people probably don’t think about it. But the handful of us that do think about “post-scarcity” want it to happen. And we probably all agree that basic income is somehow a requirement for this to happen. It’s sort of hard to be “post-scarcity” while being scarce of money. Should we go for basic income now? I think yes, let me explain.

Basic Income Has a Lot of Theoretical Benefits

Basic income is providing every citizen with regular, flat cash payments unconditionally. If you prove you are a citizen, you get a regular paycheck.

Replacing the current system of programs with a basic income has a bunch of theoretical benefits, like:

It’s really efficient because you don’t need bureaucrats involved. The government is actually pretty good at taking and giving money!

It is more equitable than retirement plans, which transfer from young to old.

It enables more people to work on what they want or get an education.

All those bureaucrats administering the current system can go do more productive things.

It reduces the marginal tax rate for the poor. (For example losing unemployment benefits and food stamps is typically the highest marginal tax rate in the US).

It replaces unemployment, which is the worst thing to subsidize (COVID’s pandemic unemployment benefits are an example of catastrophic failure here).

It replaces minimum wages, increasing possible jobs.

It reduces the potential for corruption because there are fewer middlemen and fewer opportunities for special interests…because there are none.

It provides a more stable consumer purchasing base.

It may reduce crime as a result of lower levels of desperation, particularly among the youth.

This is a pretty good list! It probably should appeal to both traditional Republicans (more freedom, fewer government programs) and Democrats (help the poor).

I think the two main counterpoints are that people will spend it poorly and that work provides meaning. These are real concerns! But frankly, the current system doesn’t work now and there is an increasing number of unemployable people. So we need to get over it.

Redistributing Better, not More

I think of basic income really as changing the method of redistribution, not the amount of redistribution. Here is a chart:

Communism is probably in the top right of this graph. Basically, take everyone’s money, and a committee decides who should get the money. “Pure Capitalism” would do no redistribution. Basically, nobody really does either pure communism or capitalism today. “Centralized redistribution + capitalism” is the most popular category today, with varying degrees of redistribution. This is basically what you would expect. Political elites prefer to dole out benefits, as it is a very effective way to increase power and influence.

But centralized resource allocation generally underperforms market-based allocation. This is why communism fails every time. In this case, it’s pretty clear that centralized redistribution is failing: we spend $20,610 per person below the poverty line. So in theory, we could just hand poor people that money and “have no poverty”. Maybe we should just…do that?

Note on charity: Charity is great. But I can't see a real "post-scarcity" sodiety with a huge unemployable segment of the population requiring charity to live.How much should basic income be?

It is better to have a permanent income than to be fascinating.

-Oscar Wilde

It’s pretty much pointless to talk about Basic Income without discussing the amount. $1,000 per year and $50,000 per year are very different propositions, with likely very different effects.

There is no “right” level. $7,000/year might be an appropriate “minimum Basic Income” since people were considered quite wealthy in the “roaring 20s” and they made an average of $7,000/year adjusted for inflation. But, let’s take at least a rough stab at what might make sense. I think a starting basic income should:

Be enough for basic necessities: food, water, sanitation, clothing, health care, & shelter in a reasonably inexpensive location in America.

Provide some capacity to improve one’s lot in life.

Be small enough to provide incentives to work and the economy to flourish.

Option 1: Just give $1 more than the official poverty line.

Our first option is basically to give $1 more than the official poverty line. Poof, no more “poverty” (definitionally).

First, let’s take a quick detour to see how the US defines Poverty. It’s a bit strange, but it kind of works.

In 1964, the US Department of Agriculture developed the “economy food plan” which was the least expensive nutritionally adequate food plan.

At that time, the average family spent 1/3 of their after-tax income on food.

The US set the “Absolute poverty line” at 3 times the “economy food plan”

The US adjusted this to the CPI over time.

So yeah, this doesn't make a ton of sense. It ignores most necessities and just assumes they add up to 2x the spending on food. This assumption makes decreasing sense over time. There are some specific problems that have emerged since the creation of this index in 1964.

1. The average family now spends 34% less of their after-tax income on food, despite significant quality improvements.

(Source: USDA)

2. As average food prices increase, the “poverty level” increases. So organic and artisanal food movements would by definition drive up the measured “poverty line”, even though in practice we probably all think that if some random people try some new fancy $1,000 cheese that shouldn’t really affect the poverty line. But it does!

3. The official poverty measure excludes non-cash benefits such as food stamps, housing assistance, refundable tax credits, or other government benefits. In other words, most poverty benefits can never officially “solve” poverty. This is pretty odd.

4. The poverty measurement assumes traditional nuclear family arrangements with an average of 2.5 related parties living in a home. The 2014 US Poverty line is $11,670/year for an individual, and ~$4,060 for each additional person. It is strange to assume that some humans can live off of $11,670 and others can live off of $4,060.

So I don’t really like the methodology here.

Option 2: Do a new bottoms-up calculation.

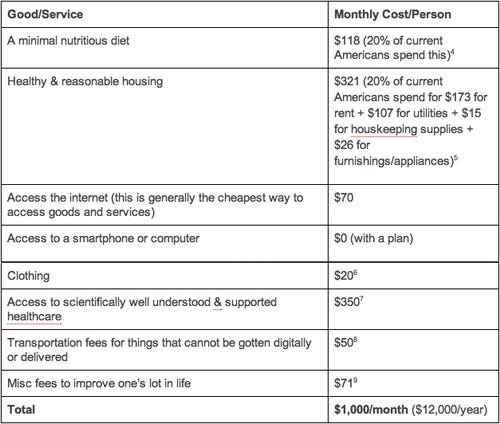

What if we just made a new calculation! Here is what I think makes some rough sense:

So while we probably would disagree a ton on these metrics, somehow I independently came up with a number very close to the US poverty line. So while I think the method of determining the poverty line is horrible, the number it landed on seems…to basically work? I choose to think that the US government agrees with me, generally speaking. I'll call that a win.

What I propose, I’m sure some will find controversial. This is ok! For example:

I only budget for a reasonable, low-cost method of accomplishing a goal. If there is a technologically free way to do something, I allocate $0 for it. Transportation is an example, with only $50 a month budgeted. Not much travel is related to survival, most travel is related to work or entertainment. Work-related travel should be covered by work pay.

We assume living in a high-cost area is a form of “entertainment”, and there is no preference given to someone who prefers to live in Santa Monica, with an average home value of $1,135,000 vs Wyoming, with an average home value of $191,000.

These numbers are absolute measures of poverty, not relative ones.

Is this too little?

$1k a month is not exactly “post-scarcity”. But I’d like to (1) solve poverty and (2) afford this. To practically implement Basic Income, we need to make this as affordable and practical as possible. While we are continuing to automate a wide range of job functions, we still need a large and motivated labor force.

You aren’t flying private jets to Aspen on this, but the average US per capita social security benefit is $12,666, and this Basic Income figure is actually higher than the national poverty rate. So there are many things that triangulate on a $1,000 per month figure.

Will this stop people from working?

It’s a legitimate concern people might stop working, but the opposite may occur. With no minimum wage or minimum benefits, companies would have more flexibility to hire workers, and labor participation would likely go up. The marginal tax rate on the poor would decrease, and this would encourage working. Many Americans could keep expenses low and retire young on a low income, few actually do. So there isn’t a ton of evidence that this would drive early retirement.

But, I do think we would probably see a decrease in “low paying jobs that people hate” and an increase in “low paying jobs people like”. Which seems like a good thing? I mean that is maybe the progressive dream?

I feel $12,000/year is about right to start.

Should we do this now?

No one, as a child, ever aspired to scrub toilets or flip burgers or restock merchandise. But you had to earn money to live your life, and these were the jobs being offered to tens of millions of people.

-Marshall Brain, Manna

When should basic income start?

1) when we have to

2) when it's affordable

When will we have to?

We will need to provide basic income (or something worse than it) at some point.

If you have a robot or AI that does a job better than a human for less money, most businesses will probably use them. Some won't. Some will advertise how this is handmade. But most people will buy the better and cheaper thing.

That will force people out of jobs. Traditionally, this has been great! People went from hard farming to a variety of better-paying jobs. But this was true only because a tractor might be better at farming but was worse at accounting or filming a movie or whatever. That is not true anymore. AI can now do office work, creative work, and administrative work better, with more capability every day.

Will new categories of work emerge? Maybe…but it's hard to think what those will be. I mean a farmer in 1900 certainly couldn't exactly imagine the job of a social media marketer, but they could imagine the idea of a marketer talking to people.

If the historical average productivity growth continues, in 20 years productivity will improve by 48%. This means almost half the number of people are needed to produce the same economic output every 20 years.

How many of those cycles can occur before we run out of new classes of jobs?

My intuition is that we will start running out of jobs in 20 years. Some might argue that it’s 40, or 60. And they may be right, but I think it’s really hard to say if 90% of jobs today were gone, there will be THAT many new classes of jobs created that humans are better at. Remember they are competing against robots with superhuman smarts and strength for these jobs.

My guess: we need basic income sometime between 20 and 60 years, which to be as a society basically means we need it “now-ish”.

When will it be affordable?

The other reason to do basic income now would be that it is affordable. And it certainly is, if we dismantle the current (most expensive) system. This includes:

All current means-tested social safety net programs (e.g. food stamps) would be dismantled.

All age-related social programs, such as Social Security and Medicare would be dismantled.

Any government-paid benefit, such as pension fund obligations or VA benefits, that are less than or equal to Basic Income would be replaced with Basic Income.

A decent measure of affordability is probably the cost of basic income in % GDP. The level of Basic Income compared to our total economic output gives some sense to the scale of its effect.

Let’s look at the cost of providing Basic Income today for adults.

The US Federal and State governments spend 13.5% of GDP annually on programs that would be immediately and directly replaced by Basic Income.

Bottom Line: Because our current social spending programs cost 11.4%, and Basic Income would be expected to cost 7.7%, we expect to save 3.7% of GDP by switching to Basic Income.

Over time, this should become more affordable as GDP per Capita has grown over time.

Source: Visualizing Economics

I also expect things to also get cheaper, in general. Software has already driven the cost of entertainment, education, and information to nearly zero. For example, medicine is largely an information science and should trend towards a $0 marginal cost over time. 25% of a residential construction project is field labor. Approximately 80% of a food’s cost is labor.

There have been a few studies that also conclude basic income is affordable. Pascal J. made estimates for Canada, and determined a basic income would be affordable without any tax increases by replacing welfare, unemployment, and related services.

The $1,000 a month seems affordable today.

Summary

In summary, basic income seems to have a ton of benefits. Giving a benefit of about $1,000 per month is affordable today, and we will probably need it in 20 years anyway. So we might as well get on it, and start working on it now. Post-scarcity, here we come!

Related Links:

1: http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1130947/posts http://povertylaw.org/communication/webinars/food-insecurity

2: http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3629

3: http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/14poverty.cfm

4: “Quintiles of income before taxes”, Bureau Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/cex/#tables

5: “Quintiles of income before taxes”, Bureau Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/cex/#tables

6: Based on my average spending a month. The 20% is technically $37 according to “Quintiles of income before taxes”, Bureau Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/cex/#tables.

7: For example, the mean Health Care spending (including insurance, drugs, & services) was $119 according to “Quintiles of income before taxes”, Bureau Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/cex/#tables. Actual healthcare spending across the US was $708, according to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_total_health_expenditure_(PPP)_per_capita and $468 according to http://www.statisticbrain.com/health-insurance-cost-statistics/. For our purposes, we will make the assumption that $119 is accurate in what consumers perceive to pay, but that the other numbers are more accurate for actual expenditures. Assuming that the majority of much spending is adopted by the wealthier 80% of the population, we can assume a normal “livable” expenditure target to be $350, which is 50-75% of the “total spend” numbers and 294% of the perceived consumer spend

8: http://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/PA694.pdf

9: http://www.ssa.gov/pressoffice/factsheets/colafacts2014.pdf

10: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/11-15-2012-MarginalTaxRates.pdf

11: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD

13: http://www.cnbc.com/id/101015065

14: States noted to have spent 29% of the federal budget in http://budget.house.gov/uploadedfiles/rectortestimony04172012.pdf

15: http://www.multpl.com/us-real-gdp-growth-rate

16: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t01.htm

17: Wikipedia. "Instituto pela Revitalização da Cidadania". ReCivitas. Retrieved 2013-07-24.

18: Wikipedia. "Namibian Basic Income Grant Coalition". Bignam.org. Retrieved 2013-07-24.

19: http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412903-Kids-Share-2013.pdf